Sedona Lit is a series by Dr. Elizabeth Oakes, an award winning poet and former Shakespeare professor. A Sedonian of three years, she will highlight the literature, written or performed, of Sedona, past and present.

By Elizabeth Oakes

By Elizabeth Oakes

(March 21, 2016)

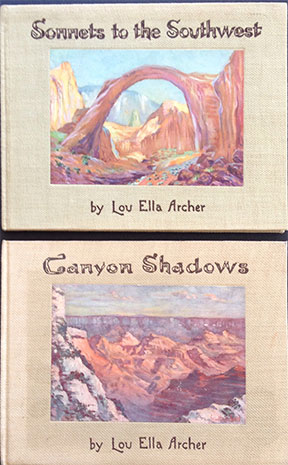

We laughingly call Sedona the “wild, wild west,” but in the early 20th century, it really was. Nevertheless, two young women ventured here. Lou Ella Archer wrote some of the first poetry about the new state of Arizona, and Lillian Wilhelm Smith painted some of the first images of the uncharted landscape. The two worked together, with Smith illustrating Archer’s two books and providing a cover painting.

Both Archer and Smith were born into privilege. It is easy to imagine both of them as characters in one of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels of the Jazz Age. A 1907 book of leading Minnesotans (available through Google) lists George Archer’s string of successful businesses, a lifestyle his daughter continued. When she married Harold A. Eliot, an attorney, in the early 1930s, the newspaper  article pointed out they were “both prominent in social circles” in Phoenix and “well known in Arizona.” Likewise, although Smith ended her life in financial straits, she came from a prominent family in Manhattan.

article pointed out they were “both prominent in social circles” in Phoenix and “well known in Arizona.” Likewise, although Smith ended her life in financial straits, she came from a prominent family in Manhattan.

Smith was born in 1882 and Archer in 1891. Imagine the gilded-cage world of these two gifted, adventurous women! It’s no wonder they rebelled. Having had to nurture her six younger siblings due to her mother’s health concerns, Smith wrote in her diary at age sixteen: “My brain seems to nearly burst at times when I think of something new, and weird and strange – ache to get my pencils but am bound by the little creatures on my lap. Oh I am burning to shake off all the trammels of conventionality and stand – alone – free and for Art.” She scandalized her social circle in 1913 when she left with Zane Grey, her cousin’s husband, to illustrate his western novels, a trip that involved living the life of a cowgirl with no amenities. In “Quiet Roads,” Archer said it this way: “Give me the winding road and let me stray / From custom-beaten paths.”

Archer and Smith had different looks for their double lives; two photos show the contrast. In the newspaper article, Archer is dressed in the high style of the 30s. Smith, photographed out in the wild, looks like a Native American. Both fit into the landscape and culture in which they were photographed. Of course, we can assume, that, vice versa, Smith had conventional clothing, and Archer didn’t wear her “city clothes” while exploring the desert.

| xx |  |

xx |  |

I remember viewing the exhibit, “Arizona’s Pioneering Women Artists” at the Museum of Northern Arizona in 2012 and being struck by how many of the bios described women from wealthy backgrounds. One woman had written back to those she left behind: “I can breathe here!” Perhaps it was not only their imagination. For example, Arizona women could vote in 1912, a year before Smith came, while women in the US overall couldn’t until 1920.

For Archer and Smith, it’s not improbable that there was artistic freedom as well, for in New York, modern art was beginning to have sway, and free verse was replacing rhyme and meter. Here, away from that world of fashion in so many ways, both could dress, write, paint, and live as they pleased.

Archer’s books have two recurring themes: the people who left traces of their lives here from ancient times and the transcendent beauty that grabs one and won’t let go. One of her poems on the first is ”Montezuma’s Castle.” Interestingly, and I don’t know how archaeologically accurate this is, she imagines that it was the women who built the structure:

What lies entombed in your adobe wall

By woman built, withstanding countless years?

They toiled with faith and love, no fears

Were in the heart of her whose hand, so small,

Instilled in you her youth, her beauty, all

Her life; each tiny fingerprint outwears

The ragged wound once made by hostile spears,

That, launched against this home, were doomed to fall.

To look on this tranquility gives birth,

Within our hearts, to love for all mankind;

For what we put into the things we make

Will hold or break them, be they made of earth

Or high ideas; thoughts are bands that bind

For centuries while builders sleep and wake.

To Archer, the past wasn’t really gone, as the spirit of the people from long ago remained, as in “To a Cliff Dwelling”:

What recollections hide within a song!

Now leaps my heart at sight of places where

Lie crumbling walls of centuries ago;

I stir forgotten ashes – from among

Them rise old dreams – I feel the presence there

Of other souls who also sought to know.

Archer and Smith developed a friendship that lasted the rest of their lives. Archer expressed how frustrating it was to try to capture the strange beauty of the southwest in words and paint: “You change a light, I change a line; we steal / Away to draw from out this haunting land / The story that we clearly understand / But cannot tell.” As Georgia O’Keeffe said of the area around Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, the landscape looks like it’s “almost painted for you – you think – until you try.”

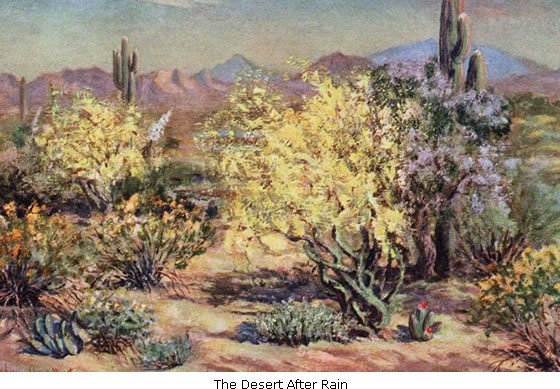

One painting and one poem have the title, “The Desert after Rain.” Perhaps both were done in the midst of the same monsoon season:

Have all the mountains given up their gold?

Is that a yellow sunset-cloud I see?

Across the desert grease-wood buds unfold

And spring is in the palo verde tree.

Does nature throw such colors on the ground?

Do waxen blooms their subtle fragrance share?

The blue is where the lupin may be found

And Candles of the Lord bloom everywhere.

Is it a blossom? I can hardly tell;

A violet haze, or just some twilight bower?

Sometime you’ll learn to know its perfume well,

But now, it is the ironwood in flower.

May you come back to us and breathe again

That magic desert air that comes with rain.

A sense of the ancient ones, a vast vista that suggests that anything is possible, unexpected beauty in what can be assumed before seeing it to be barren, and light that turns the very rock itself into a panorama of color: all these are contained in Smith’s “Sedona from Schnebly Rim.” Archer, and, no doubt, Smith, too, wished for everyone her experience, what she would no doubt call the experience of her lifetime, in “My Land”:

A sense of the ancient ones, a vast vista that suggests that anything is possible, unexpected beauty in what can be assumed before seeing it to be barren, and light that turns the very rock itself into a panorama of color: all these are contained in Smith’s “Sedona from Schnebly Rim.” Archer, and, no doubt, Smith, too, wished for everyone her experience, what she would no doubt call the experience of her lifetime, in “My Land”:

If there are those who ache to know you well,

May these poor verses help them to their goal;

And if the day should come when they may see

You as you are, and fall beneath your spell

Of tragic beauty, let your wistful soul

Give unto them what you have given me.

We might answer her by saying, “and so it has.”

1 Comment

Very educational .. thanks a lot Ms Oakes…