Sedona Lit is a series by Dr. Elizabeth Oakes, an award winning poet and former Shakespeare professor. A Sedonian of three years, she will highlight the literature, written or performed, of Sedona, past and present.

By Elizabeth Oakes

By Elizabeth Oakes

(September 19, 2016)

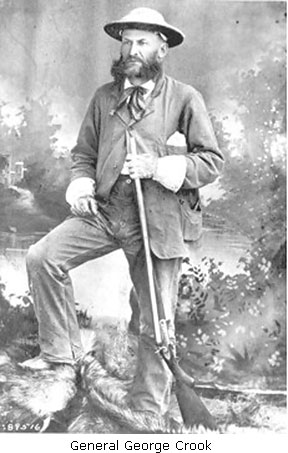

President Ulysses S. Grant called General George Crook the “greatest Indian fighter” of the West. Knowing he was a pivotal figure in American history, Crook wrote what was called in the time a “rugged biography.” It is a tale of battles, maneuvers, brutality on both sides, physical hardship, infighting over promotions, betrayals galore, and greed on the part of the Indian agents, throughout Crook’s long career in several states.

My column, however, concerns his time in the Arizona Territory generally and Camp Verde specifically. I leave it to the historians to analyze him as a soldier. I am interested in him as an author. He was not an introspective man, but he gave a vivid account of what life was like in this area in the early 1870s. It is our history –

We can get a good idea by the chapter heading, “Arizona Had a Bad Reputation.” When assigned here in 1871, Crook did his duty with trepidation, for the climate “made him fear for his health.” Let’s just say he was not overstating it!

We can get a good idea by the chapter heading, “Arizona Had a Bad Reputation.” When assigned here in 1871, Crook did his duty with trepidation, for the climate “made him fear for his health.” Let’s just say he was not overstating it!

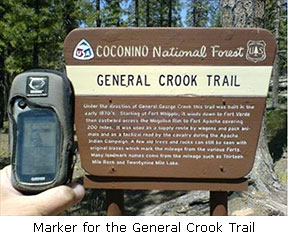

First, it was hard to get here. The intercontinental railroad was only a few years old, and there were no tracks into this area. From San Diego he took a stagecoach about 200 miles to Yuma in heat that was “like being in an oven,” even at night. From there to Tucson, the flies and dust added to the discomfort, with the temperature 116 at times. Imagine this wearing a wool Army uniform!

Then there was the lack of water and food. One night, with the “men and animals nearly famished with thirst,” a providential thunder storm saved them. They survived another time by drinking “water standing in holes.” They avoided scurvy by finding a wild onion that evidently had some Vitamin C in it.

As they neared Camp Verde, he and his men, on foot, were lost several times among the peaks of the Mogollon Rim. Perhaps we shouldn’t complain about the inconvenience of airline travel today!

I wasn’t surprised at the battles, but the chopping off of heads did shock me. A Mr. Colyer, who had been sent by headquarters, Crook believed, to countermand his authority, was determined to “make peace with the Apaches by the grace of God.” This failed so miserably that there was a “trail of blood” of settlers, with Colyer becoming known as far away as the Pacific Coast for making “life and property unsafe.” Upon his return to “Washington his head was chopped off,” I assume literally!

In another skirmish, a group of Apaches had escaped to the mountains but then returned to surrender. Crook wouldn’t let them stay until they brought “in the heads of certain of the chiefs who were ringleaders.” A few days later, they “brought in seven heads” and were admitted into the camp.

In another skirmish, a group of Apaches had escaped to the mountains but then returned to surrender. Crook wouldn’t let them stay until they brought “in the heads of certain of the chiefs who were ringleaders.” A few days later, they “brought in seven heads” and were admitted into the camp.

History is a mine field. It’s written by the victors, and the story is handed down to generations by those who have access to printing and distribution. We can, for the most part, trust names, dates, places, but what about motivations? What about the mind-set of the time? What about the difference in values? How can we judge the past on the limited information we have? What would be the point of view of Geronimo and Cochise? Can we ever see ourselves in history’s mirror?

From what I read in his autobiography, Crook was conscious of the repercussions of the “Indian Campaign.” For examples, he spent the latter part of his life giving talks on the inhumane treatment of those he had conquered. He petitioned the government time and again to release from incarceration the Apache scouts who had worked for him, to no avail. When he returned to Arizona in the early 1880s, he reported that the Apaches “had displayed remarkable forbearance in remaining at peace,” given their treatment.

Born in 1828 in Ohio, he spent his adult life in uniform, dying still in service, although not “with his boots on,” in 1890. Both his soldiers and his adversaries eulogized him. His men said, “In our hour of danger Crook would be found in the skirmish line, not in the telegraph office.” Upon hearing of his death, the Indians at Fort Apache are said to have “let their hair down, bent their heads forward on their bosoms, and wept and wailed like children.” He “never lied to us,” they said.

It all seems like a long time ago, but I end with these two words – Standing Rock.

2 Comments

Such a poignant article Libby which leaves me with such sadness. This ‘great’ country that we are so proud of rose out of the embers of such violence and disrespect for the people who already owned it. It brings shame to my heart as an American. I am well aware of the Native American history of the Verde Valley and Northern Arizona and always wonder if we as the ‘white man’ had not run so roughshod over the indigenous people– would we have been more welcomed?

Thanks, Randall! An upcoming column will be about women’s lives in early Arizona —