Sedona Lit is a series by Dr. Elizabeth Oakes, an award winning poet and former Shakespeare professor. A Sedonian of three years, she will highlight the literature, written or performed, of Sedona, past and present.

By Elizabeth Oakes

By Elizabeth Oakes

(November 21, 2016)

In the year I’ve written this column (the first one was November 23, 2015), I’ve been continually surprised at the number of famous people who found their way to Arizona in its first year of territory and statehood. All were changed by the experience radically and forever. Such a one was the photographer Dorothea Lange, whose work evolved in subject and form.

In 1918, Lange and a friend set out on a trip across the continent – from New York to California – as a precursor to the obligatory trip abroad that young, well-off women took to become more sophisticated before settling into marriage. It took six weeks by train as they made several stops, but in those days first class meant first class – ironed sheets, real china and silver at meals, and fancy menus.

They crossed the Rio Grande at El Paso and traveled through eastern Arizona – Tucson and Yuma – where the giant saguaro and the red mesas were like a different planet. Although not particularly interested in photography at this point, Lange ended up working in a photo developing shop in San Francisco.

They crossed the Rio Grande at El Paso and traveled through eastern Arizona – Tucson and Yuma – where the giant saguaro and the red mesas were like a different planet. Although not particularly interested in photography at this point, Lange ended up working in a photo developing shop in San Francisco.

There, her eyes opened to a new way of seeing by her journey, she had an epiphany: “I realized something that’s never left me – the great visual importance of what’s in people’s snapshots that they don’t know is there. They never see them in any way but personal.” This, she said, “guided me finally into documentary work.”

By 1921, she was the go-to photographer for upscale San Franciscans. She was twenty-six years old, and she would eventually see beyond the social register to the human condition.

Various philosophers – Plato is often mentioned in this connection – have spoken of the good, the true, and the beautiful as lodestars of the imagination. John Keats, a poet of the English Romantic period, ended “Ode to a Grecian Urn” with these lines: “Beauty is Truth, Truth beauty – that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” Lange’s aesthetic would eventually become not surface beauty but what we might call the true essence of a scene through the black and white tones of a photograph. She is there as recorder, not as interpreter, not even as artist.

In 1922 Lange and her husband, the artist Maynard Dixon, spent four months on Navajo lands near Kayenta, Arizona. In Lange’s words: “We went into a country which was endless, and timeless, and way out and off from the pressures that I thought were part of life.” She wore a silver Navajo bracelet that she bought during that period every day for the rest of her life.

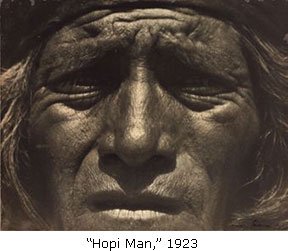

Lange and her husband came back to Arizona in 1923 and camped out in style, with tents like Chinese pagodas, caviar, wine, etc. – today we call it “glamping.” Nevertheless, she embodied the land itself in “Hopi Man,” with his face like the land itself, with arroyos, rivulets, baked earth, and eyes like caves. He and his world are fractals of each other.

Lange and her husband came back to Arizona in 1923 and camped out in style, with tents like Chinese pagodas, caviar, wine, etc. – today we call it “glamping.” Nevertheless, she embodied the land itself in “Hopi Man,” with his face like the land itself, with arroyos, rivulets, baked earth, and eyes like caves. He and his world are fractals of each other.

Ten years later she went through a crisis, realizing that she had to be free, a not easy move since her business helped support the family. Nevertheless, she decided she would “only photograph the people that my life touched.” The openness and the differences of the southwest had worked their way into her consciousness. She wanted to photograph the “very large world out there that I had entered not too well.”

Lange is famous for photographing the “Okies,” those who left the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma for California, whom John Steinbeck fictionalized in The Grapes of Wrath. In 1939, she took another government job photographing migratory laborers for the Bureau of Agricultural Economics. These photos, thought of as even “grittier” than the earlier ones, are the ones based in Arizona.

In the photos I’ve included from this group, Lange wrote the captions herself. Of “South of Eloy, Pinal County, Arizona,” she records, “Ten-year-old migratory Mexican cotton picker. He was born in Tucson. He is fixing the family car. He does not go to school now, but when he did go was in grade 1-A. Says (in Spanish) ‘I do not go to school because my father wishes my aid in picking cotton.’ On preceding day he picked 25 pounds of Pima cotton.” I wonder what happened to this boy.

In the photos I’ve included from this group, Lange wrote the captions herself. Of “South of Eloy, Pinal County, Arizona,” she records, “Ten-year-old migratory Mexican cotton picker. He was born in Tucson. He is fixing the family car. He does not go to school now, but when he did go was in grade 1-A. Says (in Spanish) ‘I do not go to school because my father wishes my aid in picking cotton.’ On preceding day he picked 25 pounds of Pima cotton.” I wonder what happened to this boy.

Another, “Eloy, Pinal County, Arizona,” depicts a truckload of migratory workers looking for all the world like immigrants in steerage arriving at Ellis Island. About them, Lange wrote, “Truckload of cotton pickers just pulled into town in the late afternoon. Fresh from Arkansas. ‘We come to help folks pick their cotton.’

There is a word from literary and political theory that has recently entered mainstream parlance – the Other (with a capital O). It is the term for those who are seen as “not like us,” as not belonging. Often they are invisible until their numbers or power reach critical mass; then the dominant culture does see them but only as a threat and retaliates with discrimination in its various forms.

Lange wanted to be a professional see-er,” she said earlier in her career. By this she may have meant she did not want to see just the personal – not just her view, conditioned by her experiences and her culture – but the essence of the subject, an essence she shared with them, as we all do.

Lange wanted to be a professional see-er,” she said earlier in her career. By this she may have meant she did not want to see just the personal – not just her view, conditioned by her experiences and her culture – but the essence of the subject, an essence she shared with them, as we all do.

In these Arizona images, Lange has “entered into” that world so completely that she has disappeared. She has disappeared, but in doing so, she has made these “invisible” people visible and permanent. The personal submerged (even that of the subjects), the good, the true, and the beautiful appear in ways we don’t usually recognize, trapped as we are in our own culture, consciousness, and aesthetics.

One can imagine that the formal portraits of the wealthy of San Francisco still hang in someone’s home, the name and genealogy known. However, her images of these migratory workers, who came, worked, and left no trace, are the only reminder they were here. Only the land remains, and Lange seemingly had little interest in landscape, only the people who moved across it.

Lange died in 1965 at the age of seventy. She was here –

Note: Some other Arizona photographs are “Hopis on a Trail to Plaza,” 1920s; “Pinal County, Arizona,” 1940; “South of Chandler, Maricopa County, Arizona,” 1940; “On Arizona Highway 87, South of Chandler, Maricopa County, Arizona,” 1940s.

Note: The most famous of her Dust Bowl photographs, “Migrant Mother,” has been reproduced many times, even as a postage stamp. The mother, her face strong but drawn by worry, looks off into the distance, as her children, facing the other way, burrow into her. Another iconic one,“White Angel Breadline,” taken in San Francisco in 1932, depicts a man, his face overshadowed by his hat, holding his cup, turned a different way from the other men.

3 Comments

Great piece about a great artist. So interesting that she came from an opposite world to her subjects, but still, seemingly, connected to them with such emparhy.

Thanks, Joe! I am more interested in her work after writing this about her!

Another great overview Libby– enjoyed this very much and reminds me of so many ‘who came before’ that truly appreciated the stark beauty of Arizona. These ‘pioneers’ of experience and documentation (not unlike yourself) have left us 9and those who follow) a wonderful gift! Terrific! This is the world Helen Frye loved so much– and indeed she spent much time canvasing the reservations alone searching for the essence that was.