By Bear Howard —

Sedona, Arizona, is a place defined as much by its people as by its crimson cliffs and cathedral-like spires of sandstone. The red rocks stand eternal, guardians of a desert landscape that has long enchanted artists, seekers, and wanderers.

Yet beneath the postcard beauty lies a community wrestling with its own reflection—a town where nostalgia for a simpler past has become a rallying cry, even as the pressures of the present grow stronger with each passing year.

For many residents, Sedona is not just a home but a refuge. They recall the days when the town was little more than a scattering of artists’ studios, family-owned cafés, and neighbors who all knew one another by name. Life moved slower then. Traffic was lighter. The word “development” was not a daily worry, nor was it an existential threat.

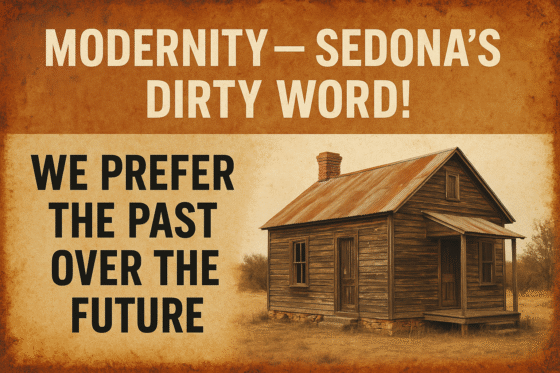

Today, the influx of visitors, the boom of short-term rentals, the rising cost of living, and the ceaseless march of commercial projects have stirred unease. For a sizable portion of Sedona’s population, the answer is not adaptation but retreat. Their adopted mantra: Modernity—Sedona’s dirty word!

One of the strongest expressions of this mindset lies in the near-sacred fixation on views. Many residents hold fast to the belief that nothing taller than two stories should ever rise in town, as if an invisible wall protects every sightline to the red rocks. That conviction, powerful and deeply felt, has become a tool to oppose almost any zoning change involving building height—and by extension, density.

The irony is that density, whether achieved through taller structures or closer ones, is the very means by which communities across the country create affordable housing and sustain modern life. Sedona’s protective posture preserves beauty but also limits options for younger families, workers, and future residents who might otherwise call the town home.

The longing for a town that “once was” speaks to a deep human desire for stability, belonging, and continuity. It is a wish to hold on to the Sedona of memory, where sandstone vistas were not shadowed by subdivisions and where the hum of cicadas drowned out the buzz of off-road vehicles.

For many, preserving the past is not simply nostalgia but survival—cultural, environmental, and spiritual. After all, if Sedona becomes just another stop on the interstate of modern America, what makes it unique?

And yet, time tells a different story. The Sedona of the 1960s was not the Sedona of the 1920s; the Sedona of ranchers and homesteaders was not the Sedona of petroglyph carvers. Every generation has seen newcomers, new ideas, and new economies. To freeze the town in a snapshot risks turning a living community into a museum—beautiful, but static.

Still, resistance has become a defining part of Sedona’s civic life. Zoning debates flare over building heights. Housing proposals face lawsuits and delays. Efforts to expand economic opportunity beyond tourism are often met with suspicion. Even basic infrastructure—road expansions, broadband upgrades, public transit—can be cast as threats to Sedona’s soul. The cry echoes again: We prefer the past over the future.

Yet the paradox remains: even holding still requires a measure of progress. Preserving open space demands planning, legal protections, and revenue. Managing housing demand requires deliberate strategies, not simply wishful thinking.

Protecting a “small town feel” in a place of global renown means balancing restraint with thoughtful growth. Without some measure of modern adaptation, the very character so fiercely guarded may erode under the weight of unmanaged change.

Sedona today stands at a crossroads—caught between the permanence of its red rocks and the impermanence of human memory. To some, modernity is the enemy. To others, it is the only way the town can survive its own popularity.

The story of Sedona is not unique; echoes of it can be heard in New England villages, Pacific Northwest hamlets, and mountain towns across the West. But nowhere is it written with such vivid color as against the backdrop of Arizona’s sandstone cathedrals.

In the end, perhaps Sedona’s challenge is not to reject modernity outright but to redefine it—to embrace a form of modernity that does not erase the past but honors it, weaving old values into new frameworks. For the red rocks will remain long after zoning disputes and housing battles fade away. The real question is whether the people of Sedona can find a way to remain, too—not as relics of the past, but as stewards of a living, evolving future.

9 Comments

Protecting a “small town feel” great atrical. Time to move on, we are now a city, not a small town anymore.

Legal definitions vary by state but population thresholds like 5,000 and 50,000 are common dividing lines between towns and cities in practice.

Even if you include the average 8200 daily visitors (including 30-40% day trippers who don’t overnight), we’re nowhere close to the normal idea of a city. Keep tryin’ though.

Maybe it’s the leadership.

In 2000 we had 10,300 residents, today about 9700. In the late 2000s, when we redid Highway SR179, we had 2 to 3 million tourists.

In 2018, the budget was $49 million, but the average prior 5 years expenditures was about $39 million.

And now the budget is more than $100 million.

What’s changed?

STRs, which have increased and taken houses, that’s about it. One of the reasons our permanent population dropped.

Traffic is worse. Well…..

Tlaquepaque North was approved without some type of pedestrian control. The permit should have never been issued without that component. SR179 is a major thoroughfare, we only have 2.

City dropped over $3m for the beautiful under bridge walkway, and then won’t stand up to ADOT to keep the Tlaquepaque crosswalk closed (exception, flooding).

The City totally screwed up uptown years ago, spent millions clogging our other major artery. Then spent several million on a “merge” “zipper” lane which didn’t correct the core problem, the mess in Uptown.

So, maybe not so much that things have changed from a perspective of what “used” to be, but the meddling of incompetent leadership that we keep electing which is supposed to set policy and give guidance for a staff run City.

Agree 🙁

I agree with most of that, but I’m less worried about locally owned STRs. Personally, I think we need fewer large hotel developments and perhaps more small scale STRs/LTRs, backyard casitas and the like.

The larger developments require many dozens of workers who will probably never be paid enough. And if they can’t pay workers a living wage, it’s okay if those businesses fail. Other entrepreneurs who can will take their place. It’s totally okay.

It’s difficult to worry about these large developments because they just keep building one after another, cannibalizing each other. If they’re not prepared to stop exacerbating the problem, many of us aren’t prepared to wreck this place with endless overdevelopment to accommodate them.

We don’t need to change building codes and construct skyscrapers for them. We don’t need to listen to people who conflate modernity with overdevelopment. We don’t have to be shy in face of antidemocratic goons who don’t care one bit about what residents think or want. We don’t need to apologize to these uncurious and unimaginative twits whatsoever.

I totally agree that many of the decisions by Council and Staff lately seem quite bad. But beyond that, it’s difficult to like or trust them because they keep doing things that they know most of the town—small town—doesn’t want. For example, one Councilor seemed to instruct Staff to push the envelope on building heights while the others mused about 3 stories, 4 stories, 5 and beyond. No one wants that. And then they say cute things like “No one owns the views.” But of course, that just means that developers own the views along with only the very wealthiest clients. And don’t get me started on the 30-million-dollar parking garage. That one still stings (but will be fun to watch as autonomous cars proliferate).

Yeah, it’s time for residents to have a more direct say. This City Manager and Council have squandered a lot of public trust.

I’m looking forward to voting on the Cultural Park, for example.

More lodging in the neighborhoods!? That’s a hard pass, Hard Pass.

Wow Hard Pass, finally something we can agree upon. As for Bear being or using AI, that’s a ridiculous complaint. Nearly everyone who writes columns, training outlines or manuals, SOP’s etc. for a living are now using AI to assist them. Why not? It’s not any different than using spell check when you get down to brass tacks. AI is a tool to aid in research and writing. Whether you like AI or not it is here and reality. I can think of far more nefarious uses of it than writing a column such as public space facial recognition, creating racist hate filled memes of political opponents wearing sombreros, being used by DOGE to fire government employees, or a POTUS falsely claiming we have futuristic non existent super hospitals for “all Americans” with it. Again we have people complaining about the messengers of truth rather than complaining about the truthfulness of the message because they are unable to disprove the message.

This “opinion” is AI-generated slop. We all know now. A real news site would fire “Bear Howard” but we don’t think he even exists.

Prove us wrong; start with a real photo of this man.

You won’t … and you won’t publish our data proving he’s fake, nor this comment calling you out.

AI Content Found

Percentage of text that may be AI-generated: 100%

AI Phrases Detected

GenAI often overuses certain phrases learned during training, which is one of dozens of signals used to identify AI text: 35

The number of times a phrase was found more frequently in AI vs human text: 3x

254x