Sedona Lit is a series by Dr. Elizabeth Oakes, an award winning poet and former Shakespeare professor. A Sedonian of three years, she will highlight the literature, written or performed, of Sedona, past and present.

By Elizabeth Oakes

By Elizabeth Oakes

(June 27, 2016)

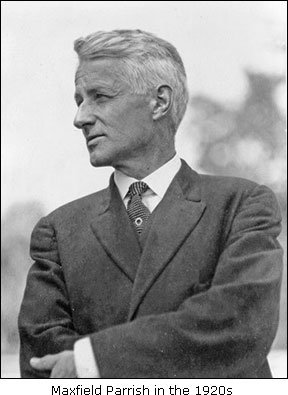

Like many who visited Arizona early in the 20th century, Maxfield Parrish was born into privilege on the east coast. Most of his adult life he lived on an estate called The Oaks in New Hampshire, which was one of the finer homes in the country at the time. He was used to museums, symphonies, travel to Europe.

This changed when Parrish came to Arizona to recover from tuberculosis in the winters of 1901 and 1902 when it was still a territory and Sedona was just being founded. In fact, in 1900 Arizona had a population of 122,931, less than many cities in the east. It was the old west, the wild, wild west. Nevertheless, he and his wife Lydia embraced this new world, and he and his art (and perhaps Lydia too, although that’s another story) were never the same.

They came to the one outpost: Castle Cliff, Hot Springs, on the Verde River southeast of Camp Verde, a resort frequented by those who gave the Gilded Age its name – the Vanderbilts, Astors, Rockefellers (and later, John F. Kennedy, who was recovering from war injuries). Although Parrish was not in their league, he certainly was one of the upper class and well able to mix and mingle.

They came to the one outpost: Castle Cliff, Hot Springs, on the Verde River southeast of Camp Verde, a resort frequented by those who gave the Gilded Age its name – the Vanderbilts, Astors, Rockefellers (and later, John F. Kennedy, who was recovering from war injuries). Although Parrish was not in their league, he certainly was one of the upper class and well able to mix and mingle.

However, he and Lydia roughed it as well. He writes: “We never expected to find ourselves out here, but here we are and having the time of our lives. Lydia is a regular Annie Oakley, rides the desert horses astride, and is a crack shot with a six shooter.”

Most of all, it was the remoteness from the world into which he was born to play a certain role that enabled growth and change. It was the openness:

Most of all, it was the remoteness from the world into which he was born to play a certain role that enabled growth and change. It was the openness:

“We are nearly twenty miles from a railroad in one of numerous canyons which cut this country in all directions, and wherever we go it is always on desert ponies. We ride to the tops of the mountains, and from there you see nothing but other mountains and not a sign of a human being anywhere. You get a sense of freedom and vastness here that I never imagined existed.”

This seems to have been true for anyone, whether socialite or desperado, who came here early on. For someone recovering from tuberculosis, there was also the air. “You never breathed such stuff in your life,” he said, “It’s right from the keg.”

T hen there was the weather – in his New Hampshire estate, he was sometimes snowed in for weeks. In a letter he exults, “This will reach you after Christmas. We are sitting out of doors under the trees here, fountains playing nearby and birds singing. It is hard to imagine that it is Christmas.”

hen there was the weather – in his New Hampshire estate, he was sometimes snowed in for weeks. In a letter he exults, “This will reach you after Christmas. We are sitting out of doors under the trees here, fountains playing nearby and birds singing. It is hard to imagine that it is Christmas.”

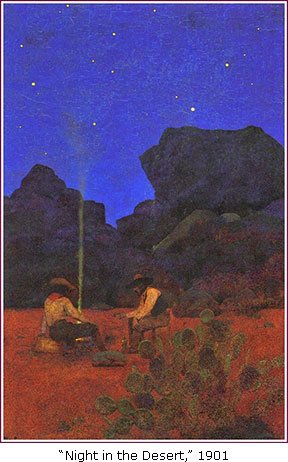

Although Parrish was commissioned to illustrate a series of articles on the Southwest, he did more than that: he changed his way of painting. “Night in the Desert,” painted in 1901, is thought of as his first use of “Parrish blue.” It depicts two crusty looking cowboys under the stars. On the back Parrish placed the site as “Hot Springs, Yavapai County, Arizona.” Instead of an idyllic world, here he painted an Arcadia that had coordinates of longitude and latitude.

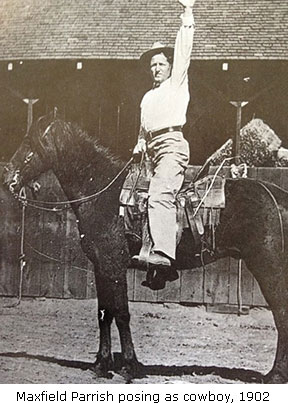

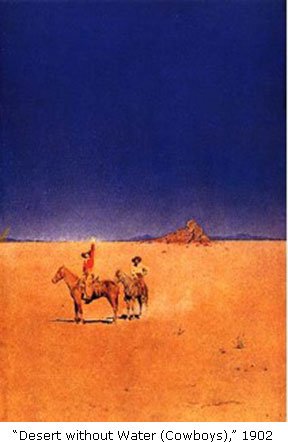

In a spirit of total immersion, he became a cowboy for “Desert without Water (Cowboys)” in 1902, using himself as a model. Lydia photographer him on horseback, dressed in cowboy garb, the photo contrasting greatly with the one of him in his life at The Oaks. In the painting the two figures are engulfed by landscape and sky, far from civilization.

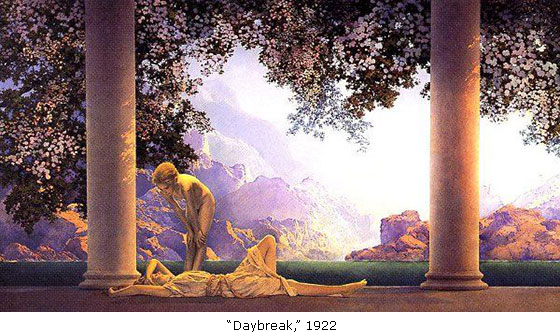

How famous was Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966) in his day? In the twenties one in four households had one of his prints, with “Daybreak” the favorite. In it he mixed his make-believe world of nymphs (his daughter posed for the figure bending over the one sleeping) with a Sedonaesque landscape just beyond the proscenium. F. Scott Fitzgerald could describe the Mediterranean as “the fairy blue of Maxfield Parrish” and be understood. Parrish was revered both by those who could afford only prints and by cosmopolites, such as Gertrude Vanderbilt, who could hang the originals on mansion walls.

How famous was Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966) in his day? In the twenties one in four households had one of his prints, with “Daybreak” the favorite. In it he mixed his make-believe world of nymphs (his daughter posed for the figure bending over the one sleeping) with a Sedonaesque landscape just beyond the proscenium. F. Scott Fitzgerald could describe the Mediterranean as “the fairy blue of Maxfield Parrish” and be understood. Parrish was revered both by those who could afford only prints and by cosmopolites, such as Gertrude Vanderbilt, who could hang the originals on mansion walls.

However, by the fifties Parrish was left behind by modern art. Incidentally, two Sedona worlds collided. Dorothea Tanning demeaned Parrish in questioning the reliance on presenting objective worlds, whether they be the inner one of Surrealism or the outer; she was longing, she continued, to let paint “have more freedom.” After all, she opined, “The peerless Dali, for instance, wasn’t he a later Maxfield Parrish but with a different imagination.”

However, by the fifties Parrish was left behind by modern art. Incidentally, two Sedona worlds collided. Dorothea Tanning demeaned Parrish in questioning the reliance on presenting objective worlds, whether they be the inner one of Surrealism or the outer; she was longing, she continued, to let paint “have more freedom.” After all, she opined, “The peerless Dali, for instance, wasn’t he a later Maxfield Parrish but with a different imagination.”

However, in certain circles, now he is again popular – for instance, George Lucas, another dreamer of imaginary worlds, is a fan. “Daybreak” is still in print, and the original, which has always been in private collections. sold in 2010 for 5.2 million.

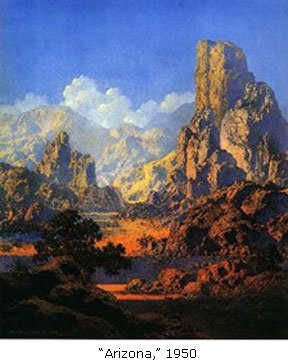

Although he was near Sedona only eight months, it was here that he imbibed the light and color that transformed his art. He never forgot. Later on, he titled two paintings “Arizona”: one in 1930 and one later in 1950, when he was eighty. Spatially, the 50s one opens to that “Parrish blue” sky and beyond to forever.

Perhaps this open vista represented what he was talking about when he said that in Arizona “there is at times a wild fiendish delight which partakes of all sorts of sensations of what is possible in art and in me and in everything.”

Perhaps this open vista represented what he was talking about when he said that in Arizona “there is at times a wild fiendish delight which partakes of all sorts of sensations of what is possible in art and in me and in everything.”

Note: Some other Arizona paintings are “Pueblo Dwellings,” “The Grand Canyon,” “Desert with Water,” and “ Water on a Field of Alfalfa.”

Note: In the interest of readability, I don’t cite sources. However, if interested, contact me, and I’ll be happy to share them.

4 Comments

I enjoyed this story. I have two Parrish prints, including Daybreak, in gilt frames from the 1920s. I hated them in my grandparents’ home when I was a pre-teen, but I wouldn’t give them up now.

Wow! You have an early 20th century treasure! Hope there’s a venue some time for you to show it!

Thanks for your comment on the column!

Very nice tribute to Parrish..

Thank you Elizabeth. That was very informative. In the 60’s, Parrish was very popular with the Hippies for his ethereal paintings. I had not idea he was influenced by Sedona. I get him completely now!

I would love to see more of his work. handsome man too!!